In May 2022, unusually heavy rains swelled two rivers in north-central Bangladesh and triggered devastating flash floods. The deluge submerged farmers’ fields, destroyed crops and affected around 2 million people — a disaster compounded by gradually rising temperatures and erratic rainfall, which climate change had probably helped to drive.

More was lost than livelihoods and crops, however, as researchers found when they asked villagers in the region how climate change had changed their lives. Some Hindu women from ‘low’ castes — social groups accorded little privilege — said they felt constantly anxious. The Hindu villagers grieved the loss of an ancient banyan tree they considered holy. The economic loss of a rice harvest was perceived by some men as shame for being unable to feed their families. “Loss and damage is so dependent on people’s values and belief systems,” says Douwe van Schie, an environmental researcher who led the study while at the International Centre for Climate Change and Development in Dhaka.

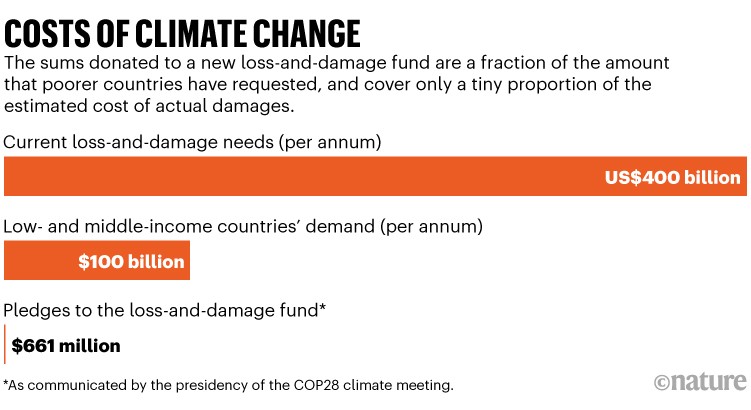

These villagers are among the estimated 3.6 billion people globally who are highly vulnerable to climate disasters — and who could, in future, receive partial compensation from a vast new source of cash. In November 2023, at the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28) climate meeting in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, nations agreed to operate a loss-and-damage fund, kick-started with donations of US$661 million. The agreement came after decades of pressure by low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which bear the brunt of climate impacts, for compensation from the rich nations that are responsible for the lion’s share of carbon emissions. The historic decision “puts climate justice at the forefront of international negotiations and elevates the voices of vulnerable and marginalized groups”, says Zoha Shawoo, a researcher at the Stockholm Environment Institute in Somerville, Massachusetts.

Although many details of the fund are yet to be worked out, some were decided at COP28. Nations have proposed that the World Bank in Washington DC could host the fund for the first four years under the supervision of an independent governing board, whose members should be nominated by the end of this month. The board will have 12 members from the developed-countries bloc of the COP and 14 from the developing-nations bloc. According to the COP28 agreement, the money is supposed to flow to LMICs that are “particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change”, which includes extreme weather events or slow-onset disasters such as sea-level rise. It could be used for reconstruction, restoration and relocation.

Researchers welcome the fund, but many say it is insufficient — and that important questions remain about how to allocate it. It’s hard to work out which disasters can be attributed to climate change, who is the most vulnerable and how to measure the losses they face. Some researchers worry that the fund will perpetuate the troubled history of development and climate finance, in which decisions made by elites in international and national governments and non-profit organizations have sometimes failed to address or have even compounded the losses experienced by people on the ground.

Researchers collaborating with van Schie, for example, interviewed an older woman in Fiji whose home was at risk because of sea-level rise. Authorities relocated her, but she still witnessed the house she had built with her late husband being torn down. Seven years later, she still cries over it — a dimension of loss that cannot easily be compensated. “Maybe what makes sense to governments or non-profits might seem very effective and rational,” van Schie says. “But it might be completely out of line with how people live their life and what they value most.”

The loss-and-damage fund adds to existing forms of climate financing such as the Green Climate Fund and Adaptation Fund, both of which are part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). These channel money from high-income countries to poorer ones for mitigation — curbing greenhouse-gas emissions — and for adaptation to climate risks, such as protecting coasts. Because these efforts will not avoid climate disasters, nations agreed in 2022 to set up a loss-and-damage fund that would fill gaps in financing. As such, the new fund cannot be used for mitigation or for pure adaptation projects, researchers say.

The board will decide on a system for allocating the funds, but according to guiding principles decided at COP28, “developing countries” that are parties to the UNFCCC would be eligible for payouts. When apportioning funds, the board should consider the scale of the impact and the country’s capacity to respond. The World Bank has until mid-June to confirm its willingness to host the fund and accept the governing board’s oversight; if it does not, the COP will search for an alternative host.

The board might divvy up the money in several ways. It could, for example, decide a maximum amount that countries can receive, irrespective of how vulnerable they are — an approach used by the Adaptation Fund, which has set a ceiling of $20 million per country for projects. Or it could prioritize on the basis of a nation’s level of vulnerability — the approach used by the Green Climate Fund, which earmarks half of its adaptation funds for small island nations, the poorest countries and Africa.

The allocation system will be important, scientists say, because the fund is nowhere near meeting the scale of the need. The $661 million that rich nations contributed is a fraction of the $100 billion annually that LMICs have requested by 2030. Studies suggest that the economic cost of damages in Africa, Asia and South America could range from $290 billion to $580 billion in 2030, and between $1.1 trillion and $1.7 trillion in 2050, depending on how much carbon the world emits. Observers say it’s highly unlikely that the fund will get donations of $100 billion per year any time soon; at the moment, nations are only “invited” to finance the fund (see ‘Costs of climate change’).

Such economic analyses account for measurable losses to a nation’s economy or gross domestic product due to damages to infrastructure or to livelihoods following a disaster, for instance. They do not consider non-economic losses, scientists say, such as to family, religious practices or mental health. “People will lose their lives, their cultures or livelihoods,” says Stacy-ann Robinson, a climate policy researcher at Colby College in Waterville, Maine. “So, whatever amount is in the fund will probably not adequately reflect the breadth of the loss and damage that countries are likely to experience.”

Another problem the board will have to consider is whether climate change helped to cause a damaging event. This field of climate science, known as extreme-event attribution, has advanced quickly in the past few years, but is not yet ready for use by decision makers, says Andrew King, a climate scientist at the University of Melbourne, Australia. The field evolved in the wealthier regions of the world, which have the weather data and climate models essential to unpick the contribution of climate change. But the analyses are usually unsuccessful in the most vulnerable countries, where data are more limited, he says. And whereas some events, such as heatwaves, are easily attributable, the models struggle with more complex disasters such as droughts, tropical cyclones and storms.

That was the case in 2022, when immense floods in Pakistan affected 33 million people — many of them already vulnerable as a result of poverty — and cost the nation $30 billion. Scientists found it difficult to quantify how much climate change contributed to the floods, because Pakistan has scarce historical weather data and not enough is known about the monsoon. In the end, the researchers concluded that anthropogenic climate change did make the rains more intense, but couldn’t quantify its exact contribution. “The onus shouldn’t be on an attribution analysis to be performed” for accessing loss-and-damage funds, King says.

Shawoo says it is not in the interests of either rich or poor countries for attribution science to be considered in allocating funds. Doing so would increase the number of disasters that rich countries could be asked to compensate for, she says, and sets too high a burden for developing nations to access the money. Instead, the board might have to consider all extreme weather events as ones that climate change helped to cause, researchers say.

With a growing number of climate-linked disasters and a limited funding pot, the board will have to decide who is most deserving of payouts from the fund. One possible way is to use indices that attempt to measure a country’s vulnerability to shocks.

For instance, the INFORM Risk Index assesses the risk of humanitarian crises in 191 nations using data on more than 50 indicators, such as the frequency of drought, measures of inequality and health expenditure per capita. (Afghanistan, the Central African Republic and Mali, for example, are considered at very high risk.)

But some researchers have concerns about such indices. As of 2020, only 14 countries had a complete data set for all the indicators used by INFORM. Small island nations had large data gaps, such as the island of Nauru, which is missing 33% of indicators. Some nations are so small that they do not have the capacity to collect data and so are in danger of falling off rankings of vulnerability, Robinson says. “We have no pre-existing system [of vulnerability assessment] that we can quickly apply” to allocate loss-and-damage funds, she says. “Somebody would need to develop and pilot it, but that is time that we don't have.”

The exercise can be difficult even for countries with seemingly good data. For example, scientists created a vulnerability map for India in 2020 using indicators such as availability of drinking water and the population of women and children5. But the study drew on the 2011 census, the last year such data were available, says Subimal Ghosh, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay in Mumbai and a co-author of the study. The Indian population has since grown drastically and migrated, which is likely to have changed patterns of vulnerability.

What’s more, vulnerability indices do not take into account historical conflict, colonial legacies and race, gender and other identities that can all contribute to disadvantage and a lack of resilience to shocks, Shawoo says. “I personally do not see a fair way to identify certain people as the most vulnerable,” she says. “It’s so subjective and political.”

Another point of contention is who will make funding decisions. In 2020, about 73% of the climate finance provided by rich nations was in the form of loans, mostly from multilateral development banks such as the World Bank, according to a climate finance report from the charity Oxfam. And 75% of these loans were granted at market rates, with no special concessions.

LMICs have pushed for a different model for loss-and-damage funding. In committee meetings leading up to COP28, they asked for the money to be disbursed largely as grants, and said it should also be directly accessible to national governments and local entities.

Those countries initially questioned plans for the World Bank to host the fund: the bank’s president is elected by the United States, its largest shareholder, and it is viewed as disproportionately influenced by developed nations. Furthermore, some countries criticized its large hosting fees and focus on loans. But at COP28, the LMICs finally agreed to accept the World Bank as host after assurances that control would lie in the hands of the governing board, where the LMICs have a majority, and that the bank’s performance would be evaluated after four years.

A spokesperson for the World Bank says the bank is honoured and committed to support countries in setting up the loss-and-damage fund as quickly as possible. Countries donating to the fund “are making an important down payment on the promise of financial support to developing countries who are hardest hit by climate shocks, even though they’ve done the least to create the problem”, they said.

Researchers say that ideally, after a disaster, some of the fund should flow to national governments and the rest to local communities to help them recover in the ways they choose. Nations should develop loss-and-damage plans in consultation with their vulnerable populations, says Lisa Schipper, a geographer who studies adaptation funding at the University of Bonn, Germany.

Schipper is concerned that, in reality, the loss-and-damage fund will use existing development architecture and practices in which funding flows from elite institutions — such as the World Bank, donor agencies and national governments — to recovery projects without consulting the people it’s meant to support. “That imbalance [in power] is astounding,” she says. “Those who really need assistance very rarely have the opportunity to make decisions about how they're going to develop.”

Ghosh says that assigning funds in a way that most helps 3.6 billion vulnerable people is like an agonizing optimization problem. “But you’ll never reach a global optimum solution here because there is no optimum,” he says. “Everyone is suffering from climate change, and if someone hasn't suffered, they will in the future.”