WASHINGTON — Coast-to-coast storms. A spate of wildfires. Flooding in Hawaii. As the United States rushes into disaster season, federal officials now have an added crisis to worry about: How to stop tightly packed disaster-response shelters from becoming hot spots of coronavirus transmission.

The virus is forcing emergency managers to rethink long-held procedures for operating shelters like these in real time. That challenge comes as the nation’s crisis-response work force is already taxed by three years of brutal hurricanes, floods and wildfires, a trend that climate change promises to accelerate.

“All of these activities that we do during and after disasters are activities that require a lot of people to be in close proximity to each other,” said Samantha Montano, assistant professor of emergency management and disaster science at the University of Nebraska, Omaha. “And that is the exact opposite of what we need to do to keep people safe from Covid-19.”

“Any hazards that we’re concerned about on an annual basis, we need to be twice as concerned about them now,” she said.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency has begun encouraging workers to “practice social distancing” and to limit to four the number of disaster victims who can be in one of its field offices at any given time, a spokeswoman said Thursday. The agency has also halted training at its National Fire Academy and Emergency Management Institute, as well as other facilities.

It also said Thursday that it would let states seek reimbursement for sheltering victims individually, for example in hotels. However, in a disaster scenario, hotels themselves might be damaged or unusable because of the crisis, or simply not close enough to serve the immediate needs.

So one of the most pressing challenges remains: What to do about shelters?

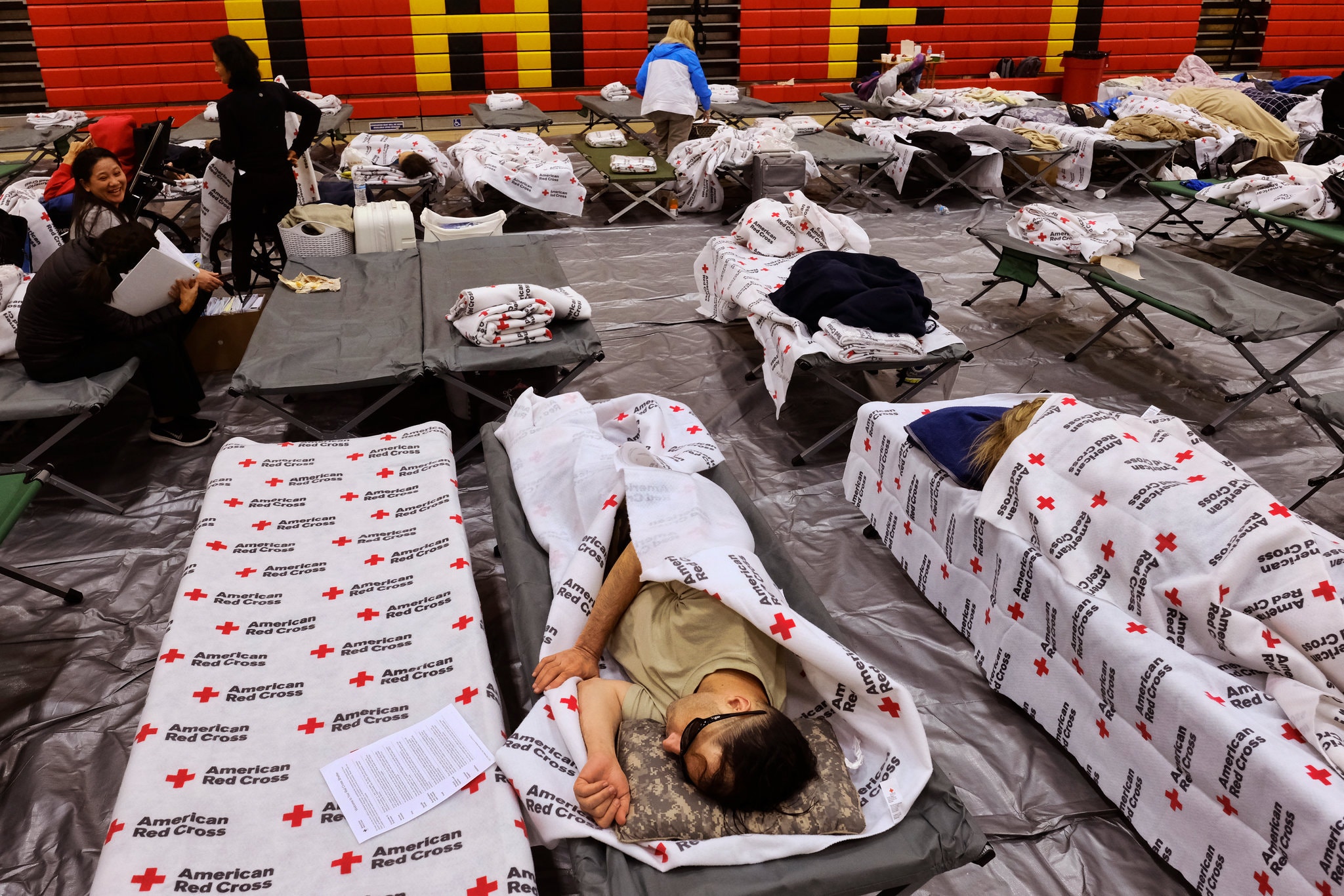

When Americans are forced to leave their homes because of flooding or fires and have nowhere else to go, charitable organizations routinely open temporary shelters that usually consist of rows of cots in school gymnasiums, churches, convention centers or other large indoor spaces.

Those shelters have offered a place of refuge, one that has become increasingly important as climate change causes more frequent and intense disasters.

On Thursday, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued data predicting widespread flooding between now and the end of May, with major or moderate floods in 23 states. California has already been hit by nine wildfires this year; the National Interagency Fire Center reported 11 new large fires around the country this week alone.

A major storm stretched across much of the country this week, with FEMA warning Friday of heavy rain from the southern plains to the Tennessee Valley. And hurricane season is just 10 weeks away.

The coronavirus has the potential to turn the shelters from a refuge into a danger of their own.

The American Red Cross, which runs most of the temporary shelters around the United States, has set new guidelines for their operation, trying to curb the risk of transmission by screening evacuees and isolating those who show symptoms, as well as spacing cots six feet apart and emphasizing good hygiene.

Officials with the organization said they knew that wasn’t a perfect solution.

Amid a pandemic, “a congregate shelter is not the best environment,” said Trevor Riggen, senior vice president for disaster services for the Red Cross, using the term for shelters that place groups of people in a single shared space. He said the Red Cross would try to move more people into hotels or motels, but added that there weren’t always enough available rooms close to a disaster, particularly if the number of people who need shelter extends into the hundreds.

Public health officials said it would be better to house disaster victims separately, despite the additional cost and logistical hurdles.

“Congregate settings are clearly a higher infection-control risk, especially when dealing with a novel respiratory virus,” said Lucy Wilson, who ran infection control for Maryland and is now a professor in the emergency health services department at the University of Maryland Baltimore County. She compared group shelters to other crowded settings like dormitories, barracks, prisons and cruise ships, where “respiratory diseases are known to rapidly spread.”

Arnold Monto, a professor of epidemiology and global health at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, said he thought the Red Cross was taking reasonable steps to protect the health of people in its shelters. But he said it seemed likely, based on what is known so far about Covid-19, that people who don’t have symptoms may nonetheless have the disease — and, more important, can probably spread it to others.

“Being in a motel would give them more distance,” Dr. Monto said. “The more people you have, the more likely that one of them might be affected.”

The federal government’s Thursday announcement that states can seek federal reimbursement for the cost of sheltering people individually — provided it’s at the direction of a public health official — could help address that concern, assuming the rooms are available. Keeping people out of group shelters “may be necessary in this Public Health Emergency to save lives,” the agency said in a fact sheet, “as well as to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe.”

Mr. Riggen said the Red Cross would try to get people into hotels when the risk of contagion is particularly high. Following an apartment fire this month in Jacksonville, Fla., a state with a large number of coronavirus cases, the organization put 45 people in hotels on the advice of local health officials, he said.

In the meantime, the Red Cross is continuing to rely on shelters, but with a few changes.

Its new guidelines call for taking the temperature of everyone coming into shelters, whether evacuees or volunteers, as well as checking for other symptoms of COVID-19. Once inside, everyone is supposed to be checked three times a day. Other steps include hand-washing stations, along with “enhanced cleaning of all hard surfaces.”

People are also told not to pull their cots together.

The Red Cross has already applied its new guidelines at two shelters, according to Mr. Riggen. One is in Hawaii, which was hit this week by flooding. That shelter housed 150 people on Tuesday night.

The other was at a school in Salt Lake City, which was set up following a 5.7-magnitude earthquake on Wednesday. A Red Cross spokeswoman, Greta Gustafson, said Friday that no one had stayed at the shelter. Workers at the shelter denied entry Thursday to a photographer for The New York Times.

“We are not aware of any positive tests” for Covid-19 at either of the two shelters, Ms. Gustafson said.

Despite the risk of the coronavirus, switching from a shelter model to putting people in hotels is more challenging that it might seem. And money isn’t the only problem.

In addition to being expensive, having people dispersed across different locations makes it harder to provide them with food and supplies, Mr. Riggen said. In some places, particularly rural areas, there may not be enough hotels nearby. And it’s not always possible to get a hotel room if somebody is pushed from their home in the middle of the night.

“We don’t want to leave people standing out on the curb waiting,” Mr. Riggen said.